I am proud to say that at the close of my internship this week, I completed arrangement of the Financial series, cleared up some confusion in the Photographs series, cleaned up minor issues that I had set aside along the way, and began some refoldering work--it's all downhill from here! Though I will not be 100% finished processing Mystery Writers of America mss. by the time my internship officially ends next week, I feel really good about the progress I made thus far, given that this is the third collection (a decently sizable one at that) I will have worked on over the course of less than five months. All the difficult work is largely finished, and what remains is brushing up the collection description, building the collection level catalog record, chronologically arranging all correspondence as per Lilly Library popular practice, and physically rehousing each folder of materials.

Rehousing will entail hand-labeling new folders and building new, archival quality boxes which will be best for long term preservation. These activities are in line with professional ethics, though rehousing is not a uniform practice across all repositories. For example, at some institutions, I know that refoldering is not always an option given budgetary constraints and the time required to hand-label each one. I am admittedly not a preservation expert by any means, but from what I understand in layman's terms: Acid free folders are ideal as buffers to control acidic paper's deleterious effects on surrounding papers. Documents made with highly acidic ingredients (i.e. most of those produced in the late 19th through mid twentieth centuries) releases acidic compounds, which may cause surrounding papers to become brittle. However, as I learned from my whirlwind day at the IU Preservation lab, acid free folders do not actually stop acidic deterioration. Simply because papers are stored inside an acid free folder does not mean that they are protected from one another, as no buffers exist directly between individual items. Rehousing in acid free folders does, however, provide some peace of mind in knowing that storage materials are not contributing additional harm to collection contents, and they also give a clean, polished look to a collection. Though appearances don't necessarily contribute to preservation objectives, they do appeal to donors and users, representing that a repository cares for its collections.

I am not exactly looking forward to the laborious penciled labeling of new folders, however I am excited about the final product which will debut as a fully processed collection in the not so distant future. I plan to finish up my processing work with Mystery Writers of America mss. after the semester closes. Over all the hours we've spent bonding together--looking at old photos from the organization's youth, peering in at intimate monetary details, and watching the group's overall development from a small group of like-minded authors to a comparatively renowned organization with members from all corners of the United States--I want to see the collection through to completion. This also seems wise, as I imagine it will be much easier for me than for anyone else to compose the collection description and catalog record content since I've spend so much time with the materials. Because I am still busy on the job-hunting front, I'll be living in Bloomington possibly as long as late July, so I will volunteer at the Lilly (at least) one day per week. With work at the IU Archives, volunteering at the Lilly, volunteering at Wylie House Museum, and applying for jobs, I will most definitely have no problem staying busy, though I also hope to spend a bit of time enjoying the outdoor air.

That's all for right now. I'll post a few more collection photos over the weekend!

Amy

Chronicles of an internship with the Manuscripts division at Indiana University's Lilly Library

Showing posts with label archives. Show all posts

Showing posts with label archives. Show all posts

Friday, April 22, 2011

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

Week Fourteen: The Dreaded Financial Series

Well, I finally caved. Despite my skillful month+ long avoidance of the six dreaded boxes of Mystery Writers of America financial materials, last week I had to "man up" and face the folders of bills, envelopes bursting with canceled checks or deposit slips, booklets full of account stubs, and ledgers galore. My initial reluctance to deal with these materials stems from the stigma that my mind must have attached to finances. No, they aren't pretty. The stationary is never ornate (at least not these from second-half of the twentieth century). It's also highly unlikely that I would happen across any juicy or otherwise thought provoking details while flipping through to gauge general folder contents and date ranges, as I often do with materials of other genres. Financial records, at least in my opinion, are not necessarily interesting in an overt or otherwise independent sense. However, surely I understand that when considered as a group or in tangent with other related documents, their evidential value can potentially shed insightful light on the practices and interests of the record creating/compiling body. For this reason, the Lilly desires to retain all financial records--regardless of how minute.

I believe I mentioned a few posts back that the Indiana University Archives, where I also work as a processor, has appraisal policies which dictate the exclusion of financially oriented items such as significant volumes of itemized receipts or account statements. Major financial documents (such as annual budgets or statements which provide a broad overview of financial standings) are retained because they can say a lot about an organization or person without taking up significant space; itemized financial documents tend to accumulate quite quickly! However, I sense that the IU Archives, which documents institutional memory in relation to departments, specific people, or groups affiliated with the University, rejects detailed financial records to avoid voluminous duplication of information shared among multiple collections, as well as because informational value is generally extremely low among these documents. Even the evidential value fades after significant time passes, when weighed against processing time and precious shelf space. Because so few reference requests come in to the Archives in regards to financial information (i.e. to what charities Prof. So-and-so donated in what specific amounts in December of 1963, or how much an academic department spent on coffee for the break room each week from 1952-1976), and because navigating disorganized financial records can be incredibly taxing, it further makes sense to me that this is one content area that is easy to justify not retaining.

Still, I can see why these records will be saved in regards to the Mystery Writers of America mss. at the Lilly. For one, the organization is much smaller than something so big as an entire university system. MWA has only been in existence since 1945, and the Lilly currently holds its entire inactive administrative record. In this situation, financial details documenting the group's formative years and those from subsequent decades may play a worthwhile role in preserving the organization's history. I hope that this rational does, in fact, sound rational. It seems a bit hard to articulate, though it all makes sense in my head (very reassuring, I know).

Anyhow, any attempt at theory aside, I spent the week wrapping up series arrangement and got a good start on wrangling the financial documents. The hardest part about processing this series for me is determining document genres. I try to mentally recreate the business processes of the organization--the cycle of disbursements, receipts of payment, various avenues of funding--but in the end, sometimes it's easier to leave a bit of that up to the researcher. When obvious, I retained folder titles as they were written upon arrival. For items such as unlabeled ledgers, I chose to err on the side of caution and arranged all of these chronologically, though some ledgers overlap and were obviously kept to document different purposes. This made sense to me, however, because from the average researcher's perspective, it seems easier to approach things chronologically than categorically for a more holistic approach. The collection is also still small enough that having to do a little digging wouldn't be too arduous. Overall, this "think like a researcher" strategy has been very helpful with my processing projects, especially when I let my nit-picky perfectionism start to take over and need to ground myself in terms of what the real goals and expectations are in description and categorical analysis.

I anticipate that I will complete arrangement of the financial series during week Fifteen, after which I'll clean up my inventory a bit (I have a horrible "notes to self" habit), then send it along to Craig and Cherry. After the inventory's official approval, I can start on refoldering and reboxing. There are a few items set aside for the Preservation department to address (two fragile scrapbooks, the brittle 100+ year old pulp magazines, and some oversized newspapers; more on all that next week). At this point, I doubt that all this will be completed by the end of the semester, but you never know! As usual, I'll keep you updated. Either way, the Mystery Writers of America mss. is well on its way to intellectual arrangement, description, and access! What a beautiful archival cycle.

Amy

PS: One more article abstract to come... and hopefully some more photos to round out the semester.

I believe I mentioned a few posts back that the Indiana University Archives, where I also work as a processor, has appraisal policies which dictate the exclusion of financially oriented items such as significant volumes of itemized receipts or account statements. Major financial documents (such as annual budgets or statements which provide a broad overview of financial standings) are retained because they can say a lot about an organization or person without taking up significant space; itemized financial documents tend to accumulate quite quickly! However, I sense that the IU Archives, which documents institutional memory in relation to departments, specific people, or groups affiliated with the University, rejects detailed financial records to avoid voluminous duplication of information shared among multiple collections, as well as because informational value is generally extremely low among these documents. Even the evidential value fades after significant time passes, when weighed against processing time and precious shelf space. Because so few reference requests come in to the Archives in regards to financial information (i.e. to what charities Prof. So-and-so donated in what specific amounts in December of 1963, or how much an academic department spent on coffee for the break room each week from 1952-1976), and because navigating disorganized financial records can be incredibly taxing, it further makes sense to me that this is one content area that is easy to justify not retaining.

Still, I can see why these records will be saved in regards to the Mystery Writers of America mss. at the Lilly. For one, the organization is much smaller than something so big as an entire university system. MWA has only been in existence since 1945, and the Lilly currently holds its entire inactive administrative record. In this situation, financial details documenting the group's formative years and those from subsequent decades may play a worthwhile role in preserving the organization's history. I hope that this rational does, in fact, sound rational. It seems a bit hard to articulate, though it all makes sense in my head (very reassuring, I know).

Anyhow, any attempt at theory aside, I spent the week wrapping up series arrangement and got a good start on wrangling the financial documents. The hardest part about processing this series for me is determining document genres. I try to mentally recreate the business processes of the organization--the cycle of disbursements, receipts of payment, various avenues of funding--but in the end, sometimes it's easier to leave a bit of that up to the researcher. When obvious, I retained folder titles as they were written upon arrival. For items such as unlabeled ledgers, I chose to err on the side of caution and arranged all of these chronologically, though some ledgers overlap and were obviously kept to document different purposes. This made sense to me, however, because from the average researcher's perspective, it seems easier to approach things chronologically than categorically for a more holistic approach. The collection is also still small enough that having to do a little digging wouldn't be too arduous. Overall, this "think like a researcher" strategy has been very helpful with my processing projects, especially when I let my nit-picky perfectionism start to take over and need to ground myself in terms of what the real goals and expectations are in description and categorical analysis.

I anticipate that I will complete arrangement of the financial series during week Fifteen, after which I'll clean up my inventory a bit (I have a horrible "notes to self" habit), then send it along to Craig and Cherry. After the inventory's official approval, I can start on refoldering and reboxing. There are a few items set aside for the Preservation department to address (two fragile scrapbooks, the brittle 100+ year old pulp magazines, and some oversized newspapers; more on all that next week). At this point, I doubt that all this will be completed by the end of the semester, but you never know! As usual, I'll keep you updated. Either way, the Mystery Writers of America mss. is well on its way to intellectual arrangement, description, and access! What a beautiful archival cycle.

Amy

PS: One more article abstract to come... and hopefully some more photos to round out the semester.

Monday, March 28, 2011

Week Eleven Auxiliar Post: Keeping Things Interesting with a few Photographs

I decided it was time to jazz things up again with some collection photographs. Below are a few of my favorites thus far.  |

| One of several fantastic pulp mystery magazines from the 1890s--the oldest items in the collection, which precede all others by approximately 50 years. This particular example, the Young Sleuth Library, is dated 1894. |

|

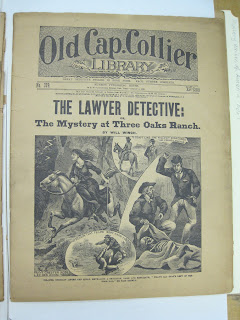

| Another pulp magazine: Old Cap. Collier Library, dated 1890. I just love the graphic design style on these! |

Week Eleven: Go Forth and Process

Technically I am cheating--it's already Monday of week twelve and I'm just now recapping week eleven. My excuse is that I took a much needed quick trip out of town over the weekend, which pushed back my blog post but helped me start this Monday morning feeling refreshed and ready to face the week. Just five more left weeks left before the end of the semester, and with it the end of my internship at the Lilly. Every day I am continually reminding myself of the limited time span that I am working with in processing the remainder of the Mystery Writers of America mss.

For the most part, I am moving along at a good pace going through the collection box by box and assigning each folder to its appropriate series. While processing the Claxon collections, I sorted all materials by series after which I arranged folders within each series. With this collection, however, I thought it made more sense to pursue both of these tasks at once. As I arrange the materials, I am also creating the collection inventory and ascertaining date ranges for each folder. It is my hope that this strategy will allow me to maximize my effectiveness to save time in the long run. Once series assignment, arrangement within series, and date range assignments are completed and typed up into a shiny new inventory, I just need to double check everything, talk my work over with Craig and Cherry, and start the refoldering process. Yes, I still have a bit of a ways to go and still need to look at retention issues for financial documents, but I feel good about where I am and my progress thus far.

One reason I devised this particular strategy is that in the case I do not finish processing, I want it to be relatively simple for my successor to pick up where I leave off. Rather than having folders in haphazard arrangement somewhere between original order at the point of accession and the finished product, the materials and inventory will either be retained in the order present at collection accession or in finished product form (or as close to it as possible prior to supervisor review). Both forms should be easily intellectually accessible for a new processor. I think that foresight such as this is essential in maintaining sanity. As archivists, we are naturally inclined (or at least trained) to document workflows. My processing strategy is a way of ensuring that my own workflow and rational is documented. Of course categorization by series is a bit subjective according to the processor's experiences and understanding of the creator; the person who may theoretically pick up on processing may differentiate between folders appropriate for the correspondence series and folders full of correspondence which relate directly to a subject or event in another series slightly differently than I would. If that sentence did not make sense, here is an example:

There is a correspondence series for which I have thus far assigned general correspondence, correspondence with specific individuals or organizations/offices, and correspondence related to a specific issue (i.e. specific rights disputes, income tax laws). However, correspondence is also interspersed throughout other topical folders. When several folders relate to a single event or topic (i.e. Edgar Awards Dinner, anthology publication, etc.), I assigned folders of related correspondence under the event or topical heading rather than a general correspondence heading. Craig talked this issue over with me and supported my perspective. Basically, the reasoning behind this arrangement comes about by thinking as a researcher. Most often, researchers are not purely searching for correspondence. They are searching for a topic within correspondence. It is more logical to streamline access by retaining materials of similar subjects together in the same series. This decision also reflects respect de fonds and/or original order. However, if processing is picked up by another individual, my reasoning may not be clear. There may also be interpretive differences between folder relationships by myself and the successor. So long as I document my choices and consider a transition of hands with foresight, issues such as these should not be a problem.

Otherwise, my processing is going smoothly. I started to second guess my choice of series when I noticed a fine line between some differentiations (Events and Subjects, Writings and Printed Material), but Craig thought I should stick with my original instincts, which I too think is for the best. Because this is a decently sizable collection (31 boxes; not huge by any means, but it dwarfs Claxon mss. II), assigning a higher number of series, comparatively speaking, will be a helpful choice benefiting user navigation. This is at least the goal.

This week (number twelve), I will continue on with processing, beginning with box 5. Mind you, this number is misleading of my progress, as I initially processed more than ten boxes at the end of the collection before jumping back to number one. My biggest problem will be figuring out how to manage the growing number of boxes that I'm actively working with in limited processing space. Surely this is something I will continually encounter in the future!

You'll hear from me again soon.

For the most part, I am moving along at a good pace going through the collection box by box and assigning each folder to its appropriate series. While processing the Claxon collections, I sorted all materials by series after which I arranged folders within each series. With this collection, however, I thought it made more sense to pursue both of these tasks at once. As I arrange the materials, I am also creating the collection inventory and ascertaining date ranges for each folder. It is my hope that this strategy will allow me to maximize my effectiveness to save time in the long run. Once series assignment, arrangement within series, and date range assignments are completed and typed up into a shiny new inventory, I just need to double check everything, talk my work over with Craig and Cherry, and start the refoldering process. Yes, I still have a bit of a ways to go and still need to look at retention issues for financial documents, but I feel good about where I am and my progress thus far.

One reason I devised this particular strategy is that in the case I do not finish processing, I want it to be relatively simple for my successor to pick up where I leave off. Rather than having folders in haphazard arrangement somewhere between original order at the point of accession and the finished product, the materials and inventory will either be retained in the order present at collection accession or in finished product form (or as close to it as possible prior to supervisor review). Both forms should be easily intellectually accessible for a new processor. I think that foresight such as this is essential in maintaining sanity. As archivists, we are naturally inclined (or at least trained) to document workflows. My processing strategy is a way of ensuring that my own workflow and rational is documented. Of course categorization by series is a bit subjective according to the processor's experiences and understanding of the creator; the person who may theoretically pick up on processing may differentiate between folders appropriate for the correspondence series and folders full of correspondence which relate directly to a subject or event in another series slightly differently than I would. If that sentence did not make sense, here is an example:

There is a correspondence series for which I have thus far assigned general correspondence, correspondence with specific individuals or organizations/offices, and correspondence related to a specific issue (i.e. specific rights disputes, income tax laws). However, correspondence is also interspersed throughout other topical folders. When several folders relate to a single event or topic (i.e. Edgar Awards Dinner, anthology publication, etc.), I assigned folders of related correspondence under the event or topical heading rather than a general correspondence heading. Craig talked this issue over with me and supported my perspective. Basically, the reasoning behind this arrangement comes about by thinking as a researcher. Most often, researchers are not purely searching for correspondence. They are searching for a topic within correspondence. It is more logical to streamline access by retaining materials of similar subjects together in the same series. This decision also reflects respect de fonds and/or original order. However, if processing is picked up by another individual, my reasoning may not be clear. There may also be interpretive differences between folder relationships by myself and the successor. So long as I document my choices and consider a transition of hands with foresight, issues such as these should not be a problem.

Otherwise, my processing is going smoothly. I started to second guess my choice of series when I noticed a fine line between some differentiations (Events and Subjects, Writings and Printed Material), but Craig thought I should stick with my original instincts, which I too think is for the best. Because this is a decently sizable collection (31 boxes; not huge by any means, but it dwarfs Claxon mss. II), assigning a higher number of series, comparatively speaking, will be a helpful choice benefiting user navigation. This is at least the goal.

This week (number twelve), I will continue on with processing, beginning with box 5. Mind you, this number is misleading of my progress, as I initially processed more than ten boxes at the end of the collection before jumping back to number one. My biggest problem will be figuring out how to manage the growing number of boxes that I'm actively working with in limited processing space. Surely this is something I will continually encounter in the future!

You'll hear from me again soon.

Friday, March 18, 2011

Article Abstract - "Preservation in the Age of Google: Digitization, Digital Preservation, and Dilemmas," by Paul Conway

When I Shadowed Doug Sanders in the IU Preservation Lab a couple weeks back, I wanted to follow the experience up with some readings on preservation and/or conservation. Admittedly, I remain a bit unclear on the differentiation between conservation and preservation. According to A Glossary of Archival & Records Terminology, by Richard Pearce-Moses (from the SAA Archival Fundamentals Series III),

Conservation is defined as:

n. 1. The repair or stabilization of materials through chemical or physical treatment to ensure that they survive in their original form as long as possible. -- 2. The profession devoted to the preservation of cultural property for the future through examination, documentation, treatment, and preventative care, supported by research and education.

Preservation is defined as:

n. 1. The professional discipline of protecting materials by minimizing chemical and physical deterioration and damage to minimize the loss of information and to extend the life of cultural property. -- 2. The act of keeping from harm, injury, decay, or destruction, especially through noninvasive treatment. -- 3. LAW - The obligation to protect records and other materials potentially relevant to litigation and subject to discovery.

preserve. v. 4. To keep for some period of time; to set aside for future use. -- 5. CONSERVATION - To take action to prevent deterioration or loss. -- 6. LAW - To protect from spoliation.

If you ask me, the difference still isn't entirely explicit in looking at those definitions alone. In a successive note, however, the author elaborates in saying that conservation is sometimes considered treatment for damage repair. Alternatively, preservation activities are considered a subdiscipline under the responsibilities of the conservator. That said, I will refer to preservation throughout this post rather than conservation, as I believe it more accurately relates to my intended idea of preservation as minimizing information loss and extending the life of materials.

Getting back on topic...

In response to my curiosity about the conservation profession and preservation activities, Cherry suggested that I look into Conservation OnLine (COOL), a resource for conservation professionals operated by the Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC). The site is a great resource which contains information pertinent to various facets of conservation and preservation work according to types of cultural property, materials, and subjects. It includes a news section, a directory of conservators and allied professionals, and links to other related groups which may be of use and interest.

The site also links to the Journal of the American Institute for Conservation (JAIC), which hosts a wealth of articles from the journal's publication run dating 1977-2005 (only articles three years old and older are accessible in a digital format; others are available to AIC members only in print format). Journal articles are freely accessible to all site visitors. Though I browsed through the full run of titles and read a number of article abstracts, my lack of training in conservation and preservation made most topics slightly intellectually inaccessible. As I mentioned in a previous entry, the conservation/preservation field is a small one which requires years of specialized trainings through extensive coursework and hands on experience. In searching through various journal databases to which IU subscribes on a quest to find more generalized articles on the topic, I came across "Preservation in the Age of Google: Digitization, Digital Preservation, and Dilemmas," by Paul Conway, as originally published in The Library Quarterly, Vol. 80, No. 1 (January 2010). Conway, a researcher and professor at the University of Michigan and has been heavily involved in the archives, preservation, and technological dialog for more than thirty years.

Though I am certainly aware of the shift to digital in all facets of life, both commonplace and professionally, I remain curious as to various opinions on how the archives community will prioritize and integrate this change. Conway's article presents an excellent introduction to the changing face of information with respects to the interests and practices of preservation professionals. It was published just over a year ago, but I think Conway's points are still quite valid.

The article looks at both "digitization for preservation" and "digital preservation," explaining that these are two separate concepts with entirely different actions and objectives. "Digitization for preservation" is explained as "digitizing" a tangible/physical resource as a way to prolong the life of information potentially even beyond that of the object itself. The articles does not give examples of this practice, but I assume any digital curation of a physical collection may fall under this heading. If I understand correctly, examples of digitization for preservation include some archival collections at IU (e.g. Herman B Wells speeches and the Andrew Wylie papers)content on the UNC's Southern Historical Collection, the University of Michigan's massive Google Book digitization project (of which IU is also a participant), and the wealth of digitized historic records available through Ancestry.com.

Alternatively, "digital preservation" means ensuring that born-digital information remains viable for the enduring future. This sort of preservation includes any and all content in digital format (including the digital products of "digitization for preservation"). Not all digital information is necessarily worth saving, but any that is requires a plan to make sure that information remains accessible. It cannot be assumed that just because a document, site, or application is accessible now means it will be accessible one, five, fifty, or a couple hundred years down the road.

Conway frames his discussion in the context that nearly all information is now going digital, yet the concept of prolonged preservation of said information is still not configured into the cyberinfrastructure plan. This is likely because those working at the front end of technological development consider the product but not its broader, long-term implications. In the present, we do not often think of the products of our daily interactions as being part of our cultural heritage--newspaper articles, advertisements, modes of entertainment, music, photographs, etc. However, all of the aforementioned items are commonly present in archival collections. Our daily interactions and modes of information sending, retrieving, and exchanging are our unrehearsed, authentic cultural heritage. At present, many of these things are increasingly present in our lives in digital formats. Without a foresighted preservation plan for this information, decades of cultural insights are threatened.

While those pioneering cyberinfrastructure, informatics, and information systems may have thoughts of longevity on the back burner, Conway poises preservationists to reconsider the realities of their professional future and take part in the digital dialog in the interests of making preservation a priority. Throughout the article, he speaks to the preservation community in terms of fundamental values and reconfiguring priorities. Conway discusses two reports on these matters: Preserving Digital Information and Preservation in he Age of Large-Scale Digitization (both affiliated with the Council on Library and Information Resources). He also touches up on traditional preservation practices and a basic history of the discipline's major trials and triumphs, cost effective prioritization, financial strain, and the impending crisis of material degradation affecting audiovisual formats.

The discussion narrows down to five poignant recommendations that Conway suggests to the preservation community. These include prioritizing for preservation quality environments (i.e. dark, cool storage with relative low humidity), shifting resources toward audiovisual digital migration, accepting digital technologies and embracing them to build collections, digitizing materials based on assumed impact (looking at a home institution's collections independently as well as in tangent with digitization projects pursued elsewhere), and come together to formulate standards and best practices for digital collection building. He encourages preservation professionals to learn new technological skills in the selfless interests of preserving cultural heritage resources.

My only hesitation with Conway's recommendations lies with what I interpret as Conway's belief that technology will settle and become to some degree static; he makes several statements to this effect. However, I do not know that anyone can predict technology will reach a state of complacency. For this reason, I expect that digital preservation strategies will always be, to some degree, in flux. Furthermore, computer science is not finite in the fashion of physical material science; material composition can be definitively broken down to each specific molecule. Digital data is based on a system of interpretation and requires the aid of a machine to be intelligible by humans. Each additional change in technology requires a new form of computer mitigation. The only hope for long term preservation lies in a collaborative effort between those interested in information creation and those devoted the information preservation.

One thing I was slightly disappointed by in this article was its fleeting mention of Google and its various initiatives and developments toward user-centered, unmitigated information seeking, fluidity vs. fixity of information, and instant gratification. Conway did not elaborate on how Google's anonymous style of all-encompassing information access will affect preservation priorities or infrastructure, and I am sure that much more can be said on this topic, however I also understand that this topic is at the same time entirely broad and still not entirely defined.

The content of this article was certainly different to what I learned out at the Preservation lab. Here at IU, digital and physical preservation are not interrelated departmental bodies. I suspect this is the case at present for most large institutions, and I am certainly curious to learn how such arrangements will develop in the coming years. Still, call me a luddite, but I cannot imagine that someday, I may have the good fortune to browse item-by-item through the Mystery Writers of America mss. on the Lilly's website. Manuscript collections are, in my mind, much too gargantuan to make item level digitization feasible. I know that this merely means repositories will prioritize digitization projects, as they do already, but I am also comforted in my belief that the physicality and connective nature of "traditional" archival collections will likely not become obsolete--if only for the reason that digitization for preservation is not feasible given financial, temporal, and data space constraints, but also because the archives may well be one last place where a person may revisit a past before digital information proliferated. There will still be fragile pages to turn, rusty paper clips to remove (or not), and enigmatic handwriting to decipher on coffee-stained letters. Technology may be changing, but human nature and the value of tactile connection will surely not change quite as fast.

Conservation is defined as:

n. 1. The repair or stabilization of materials through chemical or physical treatment to ensure that they survive in their original form as long as possible. -- 2. The profession devoted to the preservation of cultural property for the future through examination, documentation, treatment, and preventative care, supported by research and education.

Preservation is defined as:

n. 1. The professional discipline of protecting materials by minimizing chemical and physical deterioration and damage to minimize the loss of information and to extend the life of cultural property. -- 2. The act of keeping from harm, injury, decay, or destruction, especially through noninvasive treatment. -- 3. LAW - The obligation to protect records and other materials potentially relevant to litigation and subject to discovery.

preserve. v. 4. To keep for some period of time; to set aside for future use. -- 5. CONSERVATION - To take action to prevent deterioration or loss. -- 6. LAW - To protect from spoliation.

If you ask me, the difference still isn't entirely explicit in looking at those definitions alone. In a successive note, however, the author elaborates in saying that conservation is sometimes considered treatment for damage repair. Alternatively, preservation activities are considered a subdiscipline under the responsibilities of the conservator. That said, I will refer to preservation throughout this post rather than conservation, as I believe it more accurately relates to my intended idea of preservation as minimizing information loss and extending the life of materials.

Getting back on topic...

In response to my curiosity about the conservation profession and preservation activities, Cherry suggested that I look into Conservation OnLine (COOL), a resource for conservation professionals operated by the Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC). The site is a great resource which contains information pertinent to various facets of conservation and preservation work according to types of cultural property, materials, and subjects. It includes a news section, a directory of conservators and allied professionals, and links to other related groups which may be of use and interest.

The site also links to the Journal of the American Institute for Conservation (JAIC), which hosts a wealth of articles from the journal's publication run dating 1977-2005 (only articles three years old and older are accessible in a digital format; others are available to AIC members only in print format). Journal articles are freely accessible to all site visitors. Though I browsed through the full run of titles and read a number of article abstracts, my lack of training in conservation and preservation made most topics slightly intellectually inaccessible. As I mentioned in a previous entry, the conservation/preservation field is a small one which requires years of specialized trainings through extensive coursework and hands on experience. In searching through various journal databases to which IU subscribes on a quest to find more generalized articles on the topic, I came across "Preservation in the Age of Google: Digitization, Digital Preservation, and Dilemmas," by Paul Conway, as originally published in The Library Quarterly, Vol. 80, No. 1 (January 2010). Conway, a researcher and professor at the University of Michigan and has been heavily involved in the archives, preservation, and technological dialog for more than thirty years.

Though I am certainly aware of the shift to digital in all facets of life, both commonplace and professionally, I remain curious as to various opinions on how the archives community will prioritize and integrate this change. Conway's article presents an excellent introduction to the changing face of information with respects to the interests and practices of preservation professionals. It was published just over a year ago, but I think Conway's points are still quite valid.

The article looks at both "digitization for preservation" and "digital preservation," explaining that these are two separate concepts with entirely different actions and objectives. "Digitization for preservation" is explained as "digitizing" a tangible/physical resource as a way to prolong the life of information potentially even beyond that of the object itself. The articles does not give examples of this practice, but I assume any digital curation of a physical collection may fall under this heading. If I understand correctly, examples of digitization for preservation include some archival collections at IU (e.g. Herman B Wells speeches and the Andrew Wylie papers)content on the UNC's Southern Historical Collection, the University of Michigan's massive Google Book digitization project (of which IU is also a participant), and the wealth of digitized historic records available through Ancestry.com.

Alternatively, "digital preservation" means ensuring that born-digital information remains viable for the enduring future. This sort of preservation includes any and all content in digital format (including the digital products of "digitization for preservation"). Not all digital information is necessarily worth saving, but any that is requires a plan to make sure that information remains accessible. It cannot be assumed that just because a document, site, or application is accessible now means it will be accessible one, five, fifty, or a couple hundred years down the road.

Conway frames his discussion in the context that nearly all information is now going digital, yet the concept of prolonged preservation of said information is still not configured into the cyberinfrastructure plan. This is likely because those working at the front end of technological development consider the product but not its broader, long-term implications. In the present, we do not often think of the products of our daily interactions as being part of our cultural heritage--newspaper articles, advertisements, modes of entertainment, music, photographs, etc. However, all of the aforementioned items are commonly present in archival collections. Our daily interactions and modes of information sending, retrieving, and exchanging are our unrehearsed, authentic cultural heritage. At present, many of these things are increasingly present in our lives in digital formats. Without a foresighted preservation plan for this information, decades of cultural insights are threatened.

While those pioneering cyberinfrastructure, informatics, and information systems may have thoughts of longevity on the back burner, Conway poises preservationists to reconsider the realities of their professional future and take part in the digital dialog in the interests of making preservation a priority. Throughout the article, he speaks to the preservation community in terms of fundamental values and reconfiguring priorities. Conway discusses two reports on these matters: Preserving Digital Information and Preservation in he Age of Large-Scale Digitization (both affiliated with the Council on Library and Information Resources). He also touches up on traditional preservation practices and a basic history of the discipline's major trials and triumphs, cost effective prioritization, financial strain, and the impending crisis of material degradation affecting audiovisual formats.

The discussion narrows down to five poignant recommendations that Conway suggests to the preservation community. These include prioritizing for preservation quality environments (i.e. dark, cool storage with relative low humidity), shifting resources toward audiovisual digital migration, accepting digital technologies and embracing them to build collections, digitizing materials based on assumed impact (looking at a home institution's collections independently as well as in tangent with digitization projects pursued elsewhere), and come together to formulate standards and best practices for digital collection building. He encourages preservation professionals to learn new technological skills in the selfless interests of preserving cultural heritage resources.

My only hesitation with Conway's recommendations lies with what I interpret as Conway's belief that technology will settle and become to some degree static; he makes several statements to this effect. However, I do not know that anyone can predict technology will reach a state of complacency. For this reason, I expect that digital preservation strategies will always be, to some degree, in flux. Furthermore, computer science is not finite in the fashion of physical material science; material composition can be definitively broken down to each specific molecule. Digital data is based on a system of interpretation and requires the aid of a machine to be intelligible by humans. Each additional change in technology requires a new form of computer mitigation. The only hope for long term preservation lies in a collaborative effort between those interested in information creation and those devoted the information preservation.

One thing I was slightly disappointed by in this article was its fleeting mention of Google and its various initiatives and developments toward user-centered, unmitigated information seeking, fluidity vs. fixity of information, and instant gratification. Conway did not elaborate on how Google's anonymous style of all-encompassing information access will affect preservation priorities or infrastructure, and I am sure that much more can be said on this topic, however I also understand that this topic is at the same time entirely broad and still not entirely defined.

The content of this article was certainly different to what I learned out at the Preservation lab. Here at IU, digital and physical preservation are not interrelated departmental bodies. I suspect this is the case at present for most large institutions, and I am certainly curious to learn how such arrangements will develop in the coming years. Still, call me a luddite, but I cannot imagine that someday, I may have the good fortune to browse item-by-item through the Mystery Writers of America mss. on the Lilly's website. Manuscript collections are, in my mind, much too gargantuan to make item level digitization feasible. I know that this merely means repositories will prioritize digitization projects, as they do already, but I am also comforted in my belief that the physicality and connective nature of "traditional" archival collections will likely not become obsolete--if only for the reason that digitization for preservation is not feasible given financial, temporal, and data space constraints, but also because the archives may well be one last place where a person may revisit a past before digital information proliferated. There will still be fragile pages to turn, rusty paper clips to remove (or not), and enigmatic handwriting to decipher on coffee-stained letters. Technology may be changing, but human nature and the value of tactile connection will surely not change quite as fast.

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Week Nine: Delving into Mystery Writers of America mss.

After the ninth week of my internship, I find myself in the glorious throws of spring break! This doesn't actually mean much to me this year, as I'll spend my week working, catching up on internship hours that I missed in previous weeks, and applying for jobs(!). Still, there is certainly a different vibe and rhythm to the town this week with most undergraduate students off to warmer climates or heading home for a change of scene. The grocery store was practically empty when I stopped by on Saturday afternoon--a true attestation to migrating populations. I'll enjoy the comparatively empty streets and bus rides to campus in the coming days. The break is also a great forced reality check, making me step back to consider exactly what I need to accomplish in the quick six weeks to come post-break. After the break week's change of pace, I hope to start up again with renewed energy--something quite realistic considering the longer days and gradual greening taking shape in Bloomington.

Enough chatter, back to internship business! The week leading up to spring break was a good one for me at the Lilly. I'm changing gears and diving headfirst into processing the Mystery Writers of America mss. (find the current collection description here). I may refer to the organization as MWA in future references. To quote from the organization's website, the Mystery Writers of America " is the premier organization for mystery and crime writers, professionals allied to the crime writing field, aspiring crime writers, and folks who just love to read crime fiction." On Tuesday, I finished assessing the collection; in physical terms, it includes 31 boxes, some of which were partially processed by the archives at Boston University--the collection's original home. There is already a partial inventory that includes content lists for items in boxes 1-25. Though almost all files are present, organization within boxes does not match that as it appears in the inventory.

While taking my own inventory of MWA mss., I noted some obvious series into which the collection may be organized. At present, materials seem to be inventoried according to some of these obvious series (correspondence, subject files, financial, etc.), however materials often overlap categories. It also seems that the collection came in through several accessions over time, since many of these series are repeated as box numbers progress. I posed this supposition to Cherry, who confirmed that this was indeed the case. The boxes lacking representation in the existing inventory, number 26-31, contain manuscripts (drafts for publications) as well as newsletters, all of which will be simple to itemize and organize into series arrangement.

I submitted a series proposal to Cherry and Craig on Tuesday afternoon, and I received confirmation that most of my ideas are satisfactory. The only thing that we'll need to explore in more depth is the Financial series. At present, we have a number of check stubs, item level receipts, and other similar minute financial documentation not ordinarily retained in institutional repositories, such as the Indiana University Archives. However, because the Lilly's general collection policy and specific MWA mss. acquisition agreement states that no "weeding" (my apologies for using this contentious term!) will be performed on the materials, we may indeed retain these documents. From my initial assessment, it seems that we have at least one or two full cartons containing such documents. It certainly should not be a problem to process these along with the rest of the collection, but then again, should my supervisors and the active Mystery Writers of America group decide that there is low evidential and informational value in the documents, it will be more space effective to remove the items from the collection. The Lilly has an ongoing acquisition with the MWA and will receive future materials at later dates, thus the retention of financial materials in the current collection may well affect what the library acquires in the future. Again, this will not be my decision to make, though I am of course curious as to what the ultimate decision will be. Cherry and I will look at the materials after she returns from a week out of town.

Otherwise, on Thursday I got to processing initial portions of the collection. I decided to start with a box full of Audio and Video materials--cassette tapes, VHS cassettes, and one Beta cassette. I created an inventory for them, as none existed beforehand, and I will deal with proper housing later on. At present they are organized in alphabetical order by title and format. In the past, I've left items such until the tail end of my processing endeavors. This time, I wanted to give them the attention that they deserve at the outset of processing, perhaps because of a recent presentation in my Manuscripts class by IU Film Archivist Rachel Stoeltje. Rachel addressed various material formats and degradation issues that archivists may encounter when processing collections. She also discussed a potential project in the works for Indiana University to build a media preservation laboratory. How exciting! The idea is that IU may become a regional preservation hub for audio and video materials preservation and digitization. Professional consensus is that audio and video objects are not static, and they will not last forever. In order to remain viable and retain content, which lends a unique component to cultural heritage documentation of places and traditions throughout the world, audio and video materials must be continually migrated to usable mediums. At present, transfer to digital media and capturing/linking thorough metadata related to sound/visual content as well as original physicality is the best option for preservation.

Priority for audio and video preservation is something I learned about in-depth last semester, through a great Audio Preservation Principles and Practice course. In case all of my chatter made you curious, you can visit the Sound Directions Project website to learn about a collaborative project jointly pursued by Indiana and Harvard Universities; it provides a great introduction to the state of audio preservation and provides access to specially developed FACET software--potentially a great resource for repositories of all sizes and budgets when analyzing preservation priorities. To quote the website,

"The Field Audio Collection Evaluation Tool (FACET) is a point-based, open-source software tool that ranks audio field collections based on preservation condition, including the level of deterioration they exhibit and the degree of risk they carry. It assesses the characteristics, preservation problems, and modes of deterioration associated with the following formats: open reel tape (polyester, acetate, paper and PVC bases), analog audio cassettes, DAT (Digital Audio Tape), lacquer discs, aluminum discs, and wire recordings. This tool helps collection managers construct a prioritized list of audio collections by condition and risk, enabling informed selection for preservation. Using FACET provides strong justification for preservation dollars."

Many of the issues affecting audio and video materials are similar, though digital audio preservation is, at present, more realistic and "do-able" for most institutions; digital video preservation, on the other hand, requires massive data storage space, making it more difficult for many repositories to pursue at present. Thankfully Indiana University is a large institution with a fantastic computer science and data infrastructure program, meaning such an endeavor may be possible in the not-so-distant future.

And that, readers, is what we call a tangent. I think that means it's time to close. More adventures in processing to come next week as I take on paper-based records!

Best,

Amy

Enough chatter, back to internship business! The week leading up to spring break was a good one for me at the Lilly. I'm changing gears and diving headfirst into processing the Mystery Writers of America mss. (find the current collection description here). I may refer to the organization as MWA in future references. To quote from the organization's website, the Mystery Writers of America " is the premier organization for mystery and crime writers, professionals allied to the crime writing field, aspiring crime writers, and folks who just love to read crime fiction." On Tuesday, I finished assessing the collection; in physical terms, it includes 31 boxes, some of which were partially processed by the archives at Boston University--the collection's original home. There is already a partial inventory that includes content lists for items in boxes 1-25. Though almost all files are present, organization within boxes does not match that as it appears in the inventory.

While taking my own inventory of MWA mss., I noted some obvious series into which the collection may be organized. At present, materials seem to be inventoried according to some of these obvious series (correspondence, subject files, financial, etc.), however materials often overlap categories. It also seems that the collection came in through several accessions over time, since many of these series are repeated as box numbers progress. I posed this supposition to Cherry, who confirmed that this was indeed the case. The boxes lacking representation in the existing inventory, number 26-31, contain manuscripts (drafts for publications) as well as newsletters, all of which will be simple to itemize and organize into series arrangement.

I submitted a series proposal to Cherry and Craig on Tuesday afternoon, and I received confirmation that most of my ideas are satisfactory. The only thing that we'll need to explore in more depth is the Financial series. At present, we have a number of check stubs, item level receipts, and other similar minute financial documentation not ordinarily retained in institutional repositories, such as the Indiana University Archives. However, because the Lilly's general collection policy and specific MWA mss. acquisition agreement states that no "weeding" (my apologies for using this contentious term!) will be performed on the materials, we may indeed retain these documents. From my initial assessment, it seems that we have at least one or two full cartons containing such documents. It certainly should not be a problem to process these along with the rest of the collection, but then again, should my supervisors and the active Mystery Writers of America group decide that there is low evidential and informational value in the documents, it will be more space effective to remove the items from the collection. The Lilly has an ongoing acquisition with the MWA and will receive future materials at later dates, thus the retention of financial materials in the current collection may well affect what the library acquires in the future. Again, this will not be my decision to make, though I am of course curious as to what the ultimate decision will be. Cherry and I will look at the materials after she returns from a week out of town.

Otherwise, on Thursday I got to processing initial portions of the collection. I decided to start with a box full of Audio and Video materials--cassette tapes, VHS cassettes, and one Beta cassette. I created an inventory for them, as none existed beforehand, and I will deal with proper housing later on. At present they are organized in alphabetical order by title and format. In the past, I've left items such until the tail end of my processing endeavors. This time, I wanted to give them the attention that they deserve at the outset of processing, perhaps because of a recent presentation in my Manuscripts class by IU Film Archivist Rachel Stoeltje. Rachel addressed various material formats and degradation issues that archivists may encounter when processing collections. She also discussed a potential project in the works for Indiana University to build a media preservation laboratory. How exciting! The idea is that IU may become a regional preservation hub for audio and video materials preservation and digitization. Professional consensus is that audio and video objects are not static, and they will not last forever. In order to remain viable and retain content, which lends a unique component to cultural heritage documentation of places and traditions throughout the world, audio and video materials must be continually migrated to usable mediums. At present, transfer to digital media and capturing/linking thorough metadata related to sound/visual content as well as original physicality is the best option for preservation.

Priority for audio and video preservation is something I learned about in-depth last semester, through a great Audio Preservation Principles and Practice course. In case all of my chatter made you curious, you can visit the Sound Directions Project website to learn about a collaborative project jointly pursued by Indiana and Harvard Universities; it provides a great introduction to the state of audio preservation and provides access to specially developed FACET software--potentially a great resource for repositories of all sizes and budgets when analyzing preservation priorities. To quote the website,

"The Field Audio Collection Evaluation Tool (FACET) is a point-based, open-source software tool that ranks audio field collections based on preservation condition, including the level of deterioration they exhibit and the degree of risk they carry. It assesses the characteristics, preservation problems, and modes of deterioration associated with the following formats: open reel tape (polyester, acetate, paper and PVC bases), analog audio cassettes, DAT (Digital Audio Tape), lacquer discs, aluminum discs, and wire recordings. This tool helps collection managers construct a prioritized list of audio collections by condition and risk, enabling informed selection for preservation. Using FACET provides strong justification for preservation dollars."

Many of the issues affecting audio and video materials are similar, though digital audio preservation is, at present, more realistic and "do-able" for most institutions; digital video preservation, on the other hand, requires massive data storage space, making it more difficult for many repositories to pursue at present. Thankfully Indiana University is a large institution with a fantastic computer science and data infrastructure program, meaning such an endeavor may be possible in the not-so-distant future.

And that, readers, is what we call a tangent. I think that means it's time to close. More adventures in processing to come next week as I take on paper-based records!

Best,

Amy

Sunday, February 6, 2011

Week Four: Processing, ice storms, and more processing

I don't mean to sound monotonous, but this week I spent more time *surprise!* processing the Claxon mss. II collection. My hours were truncated a bit on Tuesday due to my paranoia about the ice and snow storm that walloped a large portion of the country this week, but I still managed to make decent progress. As of when I left the Lilly on Thursday afternoon, I had browsed through all files; added date ranges for every folder, subseries, series, and the collection as a whole; and arranged every folder according to the arrangement scheme I discussed with Craig at the outset of my collection analysis. Craig will sort through my work on Friday and/or Monday, and we'll discuss any issues or changes that he identifies.

I feel pretty good about my progress thus far. Though I worry that the arrangement and description of the writings series--which includes approximately two boxes of sermons--leaves a bit to be desired in the way of intellectual access by potential users viewing what will become the collection's finding aid, I feel that this is inevitable with the MPLP ("more product less process" for any of you outside of the archives profession) approach I took to these particular materials. Painstakingly sorting through each item and re-categorizing it according to title, date, Biblical passage, etc. would be incredibly time consuming, disrupt original order imposed by the creator, and present problems in the way of how to deal with items devoid of titles, dates, etc.

As I have discussed with colleagues in the past, sometimes it is best to let the researcher do the research and dig through a collection to see what they can find rather than have the archivist spell everything out. Given burgeoning backlogs, small budgets, ever-expanding professional duties, and the unavoidable constraints of time, interfering with the arrangement to meticulously process collection materials is frequently beyond the professional scope and abilities of archivists at a large volume of institutions.

I am, however, aware that some collections are still meticulously arranged to better provide more direct access to users. For example, at the Indiana University Archives, the Political Papers archivist recently received a grant to be used toward processing the papers of Birch Bayh, a former United States Senator from Indiana. I am not familiar with all the minute details, but I am aware that a number of student workers are assisting with this project by sorting through materials at the item level and meticulously grouping and arranging like materials so as to provide streamlined access to this voluminous collection, which documents Bayh's term as senator. I can certainly see the rational behind this high level of processing, as Bayh played a significant role in state and national political history, and it is expected that this collection may be used relatively heavily. Because the collection is so large, it would be arduous for researchers to access specific topical information if MPLP was employed during collection processing.

Anyhow, I really do need to expand my topics of discussion on here. While I enjoy that this is an outlet for my rational while processing, I also want to highlight some of the materials within the Claxon mss. II collection. I hope to remember to bring my camera in when I intern some time this week. Some of my favorite items include photographs, a memorial sermon written in memory of John F. Kennedy and present by Neville Claxon in Nigeria, hand painted African greeting cards, and a West African recipe booklet. Expect a bit more variety on the blog in weeks to come.

On an aside, have a good Superbowl Sunday! Though I am not a huge football fan, I enjoy the idea of it as a collective American experience. Relatedly, one of the major concepts that attracts me to archives is the documentation of collective history. I assume that the National Football League has archival holdings somewhere--be it in its own archives or at an existing archival institution--through which people of all backgrounds can connect through shared memories and events.

Cheers,

Amy

I feel pretty good about my progress thus far. Though I worry that the arrangement and description of the writings series--which includes approximately two boxes of sermons--leaves a bit to be desired in the way of intellectual access by potential users viewing what will become the collection's finding aid, I feel that this is inevitable with the MPLP ("more product less process" for any of you outside of the archives profession) approach I took to these particular materials. Painstakingly sorting through each item and re-categorizing it according to title, date, Biblical passage, etc. would be incredibly time consuming, disrupt original order imposed by the creator, and present problems in the way of how to deal with items devoid of titles, dates, etc.

As I have discussed with colleagues in the past, sometimes it is best to let the researcher do the research and dig through a collection to see what they can find rather than have the archivist spell everything out. Given burgeoning backlogs, small budgets, ever-expanding professional duties, and the unavoidable constraints of time, interfering with the arrangement to meticulously process collection materials is frequently beyond the professional scope and abilities of archivists at a large volume of institutions.

I am, however, aware that some collections are still meticulously arranged to better provide more direct access to users. For example, at the Indiana University Archives, the Political Papers archivist recently received a grant to be used toward processing the papers of Birch Bayh, a former United States Senator from Indiana. I am not familiar with all the minute details, but I am aware that a number of student workers are assisting with this project by sorting through materials at the item level and meticulously grouping and arranging like materials so as to provide streamlined access to this voluminous collection, which documents Bayh's term as senator. I can certainly see the rational behind this high level of processing, as Bayh played a significant role in state and national political history, and it is expected that this collection may be used relatively heavily. Because the collection is so large, it would be arduous for researchers to access specific topical information if MPLP was employed during collection processing.

Anyhow, I really do need to expand my topics of discussion on here. While I enjoy that this is an outlet for my rational while processing, I also want to highlight some of the materials within the Claxon mss. II collection. I hope to remember to bring my camera in when I intern some time this week. Some of my favorite items include photographs, a memorial sermon written in memory of John F. Kennedy and present by Neville Claxon in Nigeria, hand painted African greeting cards, and a West African recipe booklet. Expect a bit more variety on the blog in weeks to come.

On an aside, have a good Superbowl Sunday! Though I am not a huge football fan, I enjoy the idea of it as a collective American experience. Relatedly, one of the major concepts that attracts me to archives is the documentation of collective history. I assume that the National Football League has archival holdings somewhere--be it in its own archives or at an existing archival institution--through which people of all backgrounds can connect through shared memories and events.

Cheers,

Amy

Labels:

archives,

internship,

Lilly Library,

mplp,

processing

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Week Two: The Processing Intensifies

I am entirely confused as to how the second week of my internship has already come to a close. In part, I think this is a good thing: I am genuinely enjoying my time at the Lilly. On the other hand, this is not such a great thing: there is so much I want to do and time is so short! I think this situation conveniently embodies my New Years Resolution to be more mindful of my actions and continue to revisit overarching goals and values of the "big picture" rather than allow myself to get overly caught up in details. This seems to me to be an important thing to keep in mind as an archivist, where details can grow overwhelming, almost all consuming. I need to keep reminding myself that my goal is to process a collection efficiently and effectively ultimately to meet the needs of end users. I need to let myself step away from a construct of definitive black and white decisions and learn to assess what works best for a collection's individual nature.

This pseudo-philosophical tangent does actually relate to my intern work this week. I spent my hours digging deeper into Claxon mss. II, which consists of six boxes of manuscripts with a smattering of photographs. I often found myself being a bit too meticulous, getting caught up on a particularly interesting folder, debating over what the real theme of an unnamed folder's contents is, googling up African maps to geographically situate the Claxons in my mind, etc. Surely making these connections is important, but there comes a point when one must leave the details to the researcher.

This week, my first general endeavor was to glean a basic understanding of what types of materials are in the collection on a topical level. From there, Craig suggested that I use the "piling method" as a way to think through series level categorization. Though this method sounds basic--literally making piles of folders containing topically related documents--it provides a great way to visualize content relationships, volume of materials, and it's also extremely helpful in sorting through the most appropriate designation of more ambiguous files.

In general, Claxon mss. II contains biographical materials, correspondence, subject files, writings, conference files, and photographs. Subject files and writings command the bulk of the collection, as these provide the most substantial evidence of the creators' essential professional endeavors. Craig suggested that I continually keep in mind how a researcher might think as he or she confronts a collection. Though I understand that not all researchers are alike, I can guess that a large drawing factor for this collection is its relation to missionary activities in Nigeria and Benin--the countries where the Claxons spent the most significant portion of their time as missionaries. For this reason, I should think in terms of making my arrangement accessible to such interests. However, given that finding aids are increasingly being launched online, word searchable functionality in part eliminates the requirement for overly meticulous physical arrangement. So long as materials are adequately described, a researcher should have no problem connecting with information of interest, right?

It may not be that simple, so in the interests of improving the usefulness of my collection's eventual finding aid, I will be reading this article from the Fall/Winter 2010 issue of The American Archivist entitled: "Seek and You May Find: Successful Search in Online Finding Aid Systems," by Morgan G. Daniels and Elizabeth Yakel.

Additionally, I also plan to read this article from the Spring/Summer 2009 issues of The American Archivist: "Making the Leap from Parts to Whole: Evidence and Inference in Archival Arrangement and Description," by Jennifer Meehan. This piece discusses the process of intellectual arrangement, its inherently subjective nature, and suggests strategies for archivists to employ which may minimize the his or her unintentional shaping of a collection--something which I hope to will help me process collections more objectively.

That's all on my end for now. This internship, along with work at the University Archives, volunteering at Wylie House Museum, taking another class, and helping to organize our SAA Indiana University Student Chapter's March conference is keeping me plenty busy these days. C'est la vie--at least I'm enjoying it!

Archivally yours,

Amy

This pseudo-philosophical tangent does actually relate to my intern work this week. I spent my hours digging deeper into Claxon mss. II, which consists of six boxes of manuscripts with a smattering of photographs. I often found myself being a bit too meticulous, getting caught up on a particularly interesting folder, debating over what the real theme of an unnamed folder's contents is, googling up African maps to geographically situate the Claxons in my mind, etc. Surely making these connections is important, but there comes a point when one must leave the details to the researcher.

This week, my first general endeavor was to glean a basic understanding of what types of materials are in the collection on a topical level. From there, Craig suggested that I use the "piling method" as a way to think through series level categorization. Though this method sounds basic--literally making piles of folders containing topically related documents--it provides a great way to visualize content relationships, volume of materials, and it's also extremely helpful in sorting through the most appropriate designation of more ambiguous files.

In general, Claxon mss. II contains biographical materials, correspondence, subject files, writings, conference files, and photographs. Subject files and writings command the bulk of the collection, as these provide the most substantial evidence of the creators' essential professional endeavors. Craig suggested that I continually keep in mind how a researcher might think as he or she confronts a collection. Though I understand that not all researchers are alike, I can guess that a large drawing factor for this collection is its relation to missionary activities in Nigeria and Benin--the countries where the Claxons spent the most significant portion of their time as missionaries. For this reason, I should think in terms of making my arrangement accessible to such interests. However, given that finding aids are increasingly being launched online, word searchable functionality in part eliminates the requirement for overly meticulous physical arrangement. So long as materials are adequately described, a researcher should have no problem connecting with information of interest, right?

It may not be that simple, so in the interests of improving the usefulness of my collection's eventual finding aid, I will be reading this article from the Fall/Winter 2010 issue of The American Archivist entitled: "Seek and You May Find: Successful Search in Online Finding Aid Systems," by Morgan G. Daniels and Elizabeth Yakel.

Additionally, I also plan to read this article from the Spring/Summer 2009 issues of The American Archivist: "Making the Leap from Parts to Whole: Evidence and Inference in Archival Arrangement and Description," by Jennifer Meehan. This piece discusses the process of intellectual arrangement, its inherently subjective nature, and suggests strategies for archivists to employ which may minimize the his or her unintentional shaping of a collection--something which I hope to will help me process collections more objectively.

That's all on my end for now. This internship, along with work at the University Archives, volunteering at Wylie House Museum, taking another class, and helping to organize our SAA Indiana University Student Chapter's March conference is keeping me plenty busy these days. C'est la vie--at least I'm enjoying it!

Archivally yours,

Amy

Sunday, January 16, 2011

Week One: An Introduction

[These first-post introductions are inevitably awkward, but I am going to embrace that.]

Greetings, blogosphere! I am creating this blog in tangent with my Spring 2011 internship at Indiana University's renowned Lilly Library. I'll be working in the Manuscripts division, which lays claim to more than 7.5 million items making up a diverse collection of materials dating from medieval to modern. Highlights include, but are certainly not limited to, the papers of Upton Sinclair, Orson Welles, and George Washington's letter accepting the presidency of the United States. I am continually surprised to learn what bits of history made their way to this small city in southern Indiana by one means or another. Please pardon my boasting. I am still getting over the star shocked phase.